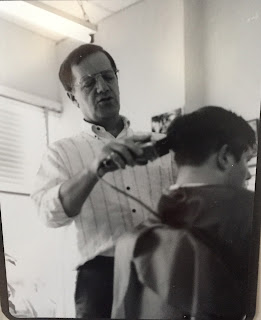

|

Westboro Station - 1952

(Source: Canada Science and Technology Museum - MAT03792) |

A long-lost landmark of the Westboro neighbourhood is the old Canadian Pacific Railway station, which gave the neighbourhood its first hub to the rest of the continent and put the name "Westboro" on the railroading map.

It is inevitable when I set up a booth at an event, or attend a meeting in the area, that I'll be asked about this train station. Not by the older, long-term residents though; they remember it well and know exactly where it was located. It is the younger generations, who sadly missed out on the exciting eras of train travel, that are most curious.

So a lot of what I'll be sharing in this photo-heavy article today has been written about previously. There are railway and local history people who have researched (and lived) the Westboro station extensively in the past, and so bits and pieces of the history can be found in various spots on the internet. So my goal for this article is to bring together all of the information, and add in a bit more that I've found. I feel including a history of the old station is imperative to the credibility of a local history website focusing on Westboro!

The background

The CPR line through Westboro first arrived in 1870 with the arrival of the Canada Central Railway, sending trains west from LeBreton Flats to Carleton Place, and all points in between. The arrival of the Railway spurred the establishment of a mill at Westboro Beach, which eventually led to the development of Westboro (more on that in a post later this January!). The CPR took over the CCR in 1881, and the mill burned for good in 1888. Meanwhile, Westboro developed slowly until the streetcars down Byron Avenue led to a real estate explosion after the turn of the century. As a result, Westboro eventually felt itself worthy of a linkage to the main passenger and freight lines being run by the CPR through the neighbourhood.

The Broad Street station at LeBreton Flats closed in January of 1920, making things even more difficult for west-enders; all CPR passenger service was moved to the Grand Trunk Railway Central Station (later better known as Union Station) in downtown Ottawa. Thus, there was a push throughout the winter of 1920 and into the spring, to have some kind of station established in the west end. A small station at Bayview known as 'Ottawa West' had been opened in 1919, but for whatever reason, it serviced only a small number of trains, and was certainly of little convenience for Westboro.

Westboro had to haul all its freight from Ottawa. There were no express facilities at Westboro and all express parcels had to be brought out. Passengers had to travel a considerable distance to the nearest station, and had to take a street car to reach it.

Thus the Westboro Ratepayers Association (the early version of the community association) sent a letter to Westboro Police Village Council, requesting Westboro Council to approach the CPR to request a railway station be built at Westboro. At their meeting of January 13th, 1920, it was decided that the Secretary-Treasurer of Westboro Council (and professional wallpaper-hanger) Alfred Barnes would communicate with the CPR. Perhaps initial contact with the CPR did not go well, as nine days later, Westboro Council attended the meeting of Nepean Township Council to ask Nepean to request the Westboro station.

Thus on January 22nd, Nepean Council passed a motion agreeing to request a station in Westboro:

|

Scan from the original Nepean Township Council minutes

showing the motion to request for a Westboro station.

January 22, 1920. |

On April 20th, Nepean Township sent five of their most prominent civic leaders in Bell, Cummings, Holloway, Cole and Reeve William Joynt to a key meeting which included CPR engineering executives, Ottawa City Council members, and representatives from the small neighbourhood of Ottawa West (the original built-up area between Island Park Drive and Western Avenue). Nepean Township pushed for the station to be located on Victoria Avenue (now Roosevelt), however the City of Ottawa contingent, as well as CPR officials, argued that a station at Parkdale Avenue was the more "logical location", and thus it was selected instead of Westboro.

Undaunted, at the May 3rd meeting, Nepean Council decided to still push for a Westboro location, and agreed to contact the Board of Railway Commissioners, the governing body of the railroads. Meanwhile, the CPR went ahead and established a station 500 feet west of Parkdale Avenue on the south side of the tracks (which would be just slightly west from where the Beer Store is today, pretty much on the west-bound lanes of Scott). A cinder platform was installed, and the first local passenger trains began stopping on Monday May 24th. A City Passenger Agent J.A. McGill was assigned to the location, and construction of a full station was to begin soon after (it is uncertain if the full station was ever built; it seems unlikely that it was). Adding insult to injury, the papers even called the station "Westboro" even though it was not near Westboro at all!

|

| Ottawa Journal, May 26 1920 |

By July, things were getting intense. Nepean Township wanted their Westboro station, but the CPR insisted it would not build two stations in relatively close proximity (though we now have transitway stations at Westboro and Tunney's, logistically it would not have made much sense to have large steam trains embark at Westboro and then have to stop again at Parkdale). The Board of Railway Commissioners heard the case on July 6th, appropriately enough, in the board room at Central Station. Nepean Township had Carleton County lawyer J. E. Caldwell battle against the CPR lawyer T. B. Flintoft. The City of Ottawa also had their lawyer F. B. Proctor involved, as well as Controller John Cameron and Commissioner of Works Macallum, as the decision would affect the newly established station at Parkdale that Ottawa hard argued so strongly for. The hearing brought out a large number of residents from along the line to Britannia, who supported the Westboro station location.

The CPR lawyer argued that the station at Parkdale was established for the people of Westboro, and that it would object to two stations within a mile of each other. The City of Ottawa also argued that the Parkdale station was to serve the entire west end, including Westboro, "and in a measure to take the place of the Broad street station."

The Citizen wrote the following day that they felt Nepean's application would not likely be granted, and closed their article by noting that the decision would be made in the near future, "but the possibilities of a station being granted, as gathered from the remarks of the commissioners sitting on the case, seems remote at the present time."

The Board took their time, and surely there was some heavy politicking happening throughout the summer, though no records either through official documentation or the media seem to indicate any activities of note during the summer of 1920.

By September, all parties continued to wait. The Westboro Council minutes at their September 7th meeting noted that the Board had hoped to have the news regarding the station, but did not yet.

The big news finally came on September 27th, when the Board of Railway Commissioners ordered the CPR to open the station at Westboro! The order included "a new station complete with passenger, traffic, freight, express and telegraph facilities. The station is to be in operation by December 1." Whatever the Township of Nepean had done to convince the Board certainly worked.

|

| Ottawa Citizen, September 27, 1920 |

When Westboro Council met again on October 5th, the minute-taker expressed the obvious joy held by the Council in the decision of the Railway Board, and added that "each of the Trustee Board expressed his pleasure that this was a great step in the future development of Westboro."

However, the battle wasn't over yet. By November, there was still no sign of construction starting in Westboro, and the Board of Control in Ottawa were meeting with the Railway Commission to argue their decision, as they wanted the Parkdale and Scott station to stay. The City of Ottawa clearly was displeased that a station would be established outside of the city limits (which at the time was Western Avenue).

On November 9th, the Board of Railway Commissioners extended the deadline to build Westboro Station to July 1st, 1921, "provided that a temporary station and platform be erected, a station agent appointed, passenger, freight, express and telegraph service provided and a spur to take care of carload traffic were constructed on or before December 1st, 1920". The Board stood firm with their decision, and ultimately the Parkdale station was cancelled, and not long after the Ottawa West station at Bayview would become a key location on the CPR line, pretty much halfway between Westboro and Union Station.

The lifetime of Westboro Station

Records from 1921 are incomplete, and even some of the local railway history experts that have written about the station (notably Colin Churcher, who I often refer to for all matters of Ottawa rail history) are stumped by when exactly construction began on Westboro Station, when it first opened, and when the Parkdale station was closed down. It appears the answer to all three lies somewhere in early 1921, as early as perhaps January. The most telling piece of evidence towards this end lies in the fact that at the Westboro Council meeting of January 10th, 1921, it was agreed that the Council would pay for the construction of "a suitable sidewalk to the CPR station from Richmond Road." Later in June, it was recorded that stone was quarried from River Street (the former name of Roosevelt) to form the foundation for the sidewalk.

The photo below is the earliest known photo of Westboro Station, and it appeared in Bob Grainger's excellent book "Early Days in Westboro Beach", a photo which he had obtained from Lois (Milton) Woolsey, and taken on August 8th, 1923.

|

Westboro Station in 1923.

(Source: Early Days of Westboro Beach) |

Colin Churcher on his website (

http://churcher.crcml.org/circle/Westboro.htm) noted that by May 1st, 1921, "Westboro acquired a day operator, train order signals and call letters BO. (Note: the call letters was the telegraphic code used to simplify transmission of messages in Morse code)."

Churcher also notes that the Board of Railway Commissioners made an order on June 1st, 1921, approving the CPR plans for the proposed station, an order on June 23rd granting an extension to construct the station until October 1st, and an order on July 12th authorizing the relocation of the station (likely moved to a slightly different location, or perhaps on the opposite side of the tracks). So the likely date of construction of the permanent station was the summer of 1921.

Here are drawings and floor plans for the station, which were published in Branchline Magazine in 1985, the author having obtained them from the Canadian Pacific Corporate Archives:

Here is the station as it appeared in the January 1922 fire insurance map for Westboro, published by Goad's. The station is visible as a small 1 storey structure, in wood (indicated by yellow colour) labelled "Station", on the north side of the track (solid line) between Victoria (Roosevelt) and William (Winston). Also visible is a small freight shed (dark grey) about 100 feet to the east:

|

| January 1922 fire insurance map |

The best two photos of Westboro Station are the one which appears at the top of this article, which is from 1952, and this one below, taken around 1940 as part of the rare Photogelatine Westboro postcard series issued at that time. I love this photo!

|

Westboro Station looking west.

From Westboro postcard series early-1940s. |

The only other photos that I've seen of the station are from aerial pics. So I've assembled the best views I've found, to show it in different ways, and occasionally with a train passing through or on the siding. In all instances north is on the bottom (so you'd have Richmond Road above and the River below). Keep in mind the station was on the north side of the tracks.

This is the earliest view I have, from May 11th, 1928:

|

May 11, 1928 aerial photo. At the time Roosevelt was a direct

line to the River, and Kirchoffer did not really exist. No paved

streets at the time either. |

This higher-resolution photo is from May 26th, 1931:

|

May 26, 1931. A third building can now be seen, and the

detail of such features as the long platform, the siding,

and the crude fence in behind can be seen more clearly. |

Here is a wider view of the area, same photo, but just showing more of the area around the station as it was in May of 1931:

|

May 26, 1931. At the far left is Churchill Avenue, and that

would be today's Workman Avenue below the tracks, with

Royal and Atlantis and the Roosevelt extension branching off.

The houses on the north side of Wilmont Avenue can be seen

at the very top of the photo. |

From May 5th, 1933, which shows a train passing on the tracks, as well as five cars on the siding:

|

| May 5, 1933 |

This great photo from September 16, 1944 shows a long steamer coming through the station:

|

| September 16, 1944 |

Here is a fire insurance plan view of the station and surrounding area from 1956:

|

| 1956 Fire Insurance Map |

The trains of Westboro Station

There are railway experts far more knowledgeable than I who could speak at length about the traffic of trains that stopped at, and went through, Westboro Station. What struck me as most interesting was in fact how little used Westboro Station likely was. Though there was heavy traffic on the CPR line, for the majority of the time the station was open, passenger service extended only in to Ottawa to the east, or Chalk River to the west (with Smiths Falls, Carleton Place, Almonte, Arnprior, Pembroke, etc. in between). If a traveller wished to go to Toronto, Montreal or elsewhere off this line, they had to embark from Ottawa West or Union Station downtown, or transfer elsewhere.

Below is a timetable from October of 1949, showing the train times and destinations from Westboro Station:

|

| Timetable from October 1949 |

Local railway historian/expert Bruce Chapman explains how complex the scheduling was just to get to Toronto: "There was a morning train to Chalk River out of Ottawa West about 830am, and the train to Brockville and Toronto about 930am; so if you wanted to go to Toronto from Westboro, you got on #555 to Chalk River, off at Carleton Place and caught #563 to Toronto, but returning in the evening, #558 from Chalk River got to Westboro before #562 from Brockville, so you had to go to Ottawa West."

Long-time Westboro historian Shirley Shorter noted in Newswest in 1986 that there were several "Stationmasters" at Westboro station over the years, remembering Mr. Fitzgerald, Mel Douglas and Harold Flake as three who held this position. She wrote that "the Stationmaster was kept busy selling tickets, looking after the baggage and flagging down a train to pick up a passenger waiting at his station. The young locals used to torment him by sitting with their legs hanging over the tracks, when they saw the train appear on the horizon. Sometimes they hopped on the back of the train when it slowed down and took a free ride into Ottawa West. One episode told me by a former resident was: A young man was standing on the platform waiting for the train to arrive. As it neared the station travelling at quite a clip, it hit a dog on the tracks, tossed it up into the air, it landed on the young man's leg with such force that his leg was broken."

As seen in the photos above, spur lines existed off of the main track running in to the lumber yards to deliver coal and lumber and building materials, and there were also sidings between Roosevelt and Churchill to hold freight for local companies. Bob Grainger noted in his book that "John Ross' father would order animal feed by rail for his store on Richmond Road and then send his men with a truck to pick up portions of it." These were called 'back tracks' or 'team tracks'. According to Bruce Chapman (helping simplify terminology for me): "The ‘siding’ at Westboro was really a back track. A siding was where trains could meet or pass, but the back track at Westboro had derails at both switches to keep cars from rolling away while being loaded or empties at Fentiman’s. Cummings had their own back track east of Churchill, and that is where the big wreck was in the early 1950’s This back track could also be called a ‘team track’, just like the back track down at Holland Avenue, near the Beach Foundry back track...a team track was where anyone could load or unload a car."

Bruce also kindly detailed the local delivery work which occurred on this track during the day: "Back in the 1950’s, when the steam locomotive shunter would leave Ottawa West station at Scott and Bayview Road just after noon, he would have cars to switch at Beach Foundry, Independent Coal and Lumber, sometimes the Cummings coal chute just east of Churchill, and some times he had a car for Fentimen’s at Roosevelt...then he would poke down to that Leafloor coal siding, and often the crew would have lunch out there. The locomotive on this job was always the 3510." Bruce included a photo of the 3510 at Ottawa West which he took, just in front of the old Humane Society building:

|

The "work extra" 3510 at Ottawa West.

Photo courtesy of Bruce Chapman. |

Bruce says he was only ever inside Westboro Station once, and found "it was just like Ottawa West, but a lot quieter."

I also spoke with Ron Statham, who also very kindly shares his memories of Westboro in the good old days with me from time to time, and he remembers the station well, and noted that he felt it was similar in style to the Carleton Place station. He remembered one trip in particular that started at Westboro Station in the early 40s: "The family had a cottage on the Mississippi river near Carleton Place and I believe and this is a stretch of my Memory going with my mother and grandparents during the war from Westboro to Carleton Place."

It is worth mentioning that there were several significant accidents which occurred by this station during its lifetime. With the neighbourhood growing after WWII, and the prevalence of the automobile of the 1950s and 1960s, it was inevitable that train would meet vehicle with increasing frequency. Bob Grainger details many of these accidents in his book, so I won't go through them all here. However, the most noteworthy of them all, and the one remembered by every Westboro resident who was old enough to remember, was the big accident which occurred on the cold morning of January 20th, 1951.

A train travelling east past Westboro Station at the incredible speed of 70 miles per hour, collided with a coal truck from the Independent Coal Company at Churchill. The evening's newspaper described it as follows: "The engineer of the CPR Dominion Flyer was fatally injured, his fireman badly injured, 30 passengers suffered bruises, and the engine and four passenger cars thrown off the track in a collision with a truck at the Churchill Avenue crossing in West Ottawa at 7:50 this morning. The cross-country train, running an hour and twenty minutes late, was travelling 70 miles an hour, making up time, when the smash occurred. The engine reeled off the track, plowing into the side of an embankment for nearly 500 yards. The driver and helper on the Independent Coal Company truck jumped before the moment of impact and escaped injury."

|

The 1951 derailment and collision. This is at Scott Street

looking west. You can see the familiar stone house on Churchill

(currently the law offices of Farber-Robillard-Leith) in the

background middle. |

Most of the passengers were up and walking in the train, preparing for the arrival at Union Station, and were thrown about inside the cars, resulting in concussions and head and back injuries. All available ambulances and police cars were sent to the scene to transport the injured to the Civic Hospital, and private automobiles were commandeered into use.

Other accidents over time at this spot were more deadly, but the 1951 accident was the most memorable due to all the factors involved, the speed, the size of the train, and the fact that it occurred at the start of a work/school day, thereby bringing out most of the Westboro population to view.

In July of 1952, with the use of the station dropping, the CPR removed the station agent and appointed a caretaker-agent to run the station, which included selling tickets, cleaning the station and managing the heat and lighting. By December of 1957, even this agent was removed.

On September 29th, 1958, the station was ordered closed, and it was demolished in the fall of 1960. The final passenger train to go through Westboro Station was the eastbound 'Canadian' on Saturday July 30th, 1966.

Trains did still run on the tracks for another year, the final trains to pass through was on August 28th, 1967, and the line was cut at McRae Avenue just after its passing. (Again all thanks for this information to Colin Churcher).

The tracks west of McRae all the way out to Bells Corners were removed shortly afterwards. The tracks to the east were removed in segments, as their industrial use diminished. The last segment to go was the portion along Scott Street from Bayview to Holland which was being used by Beach Foundry. (You can read a bit more about that part of the line in my article from last year at the Kitchissippi Times:

https://kitchissippi.com/2015/09/17/making-transit-history-at-tunneys-pasture-again/)

Situating the Station in present-day

To situate yourself to exactly where the station was, I find the following three shots from GeoOttawa help to place it. Below are views from 1958 (when the station is there), 1965 (the station has been demolished), and 2014 (the Transitway now runs):

|

| 1958 aerial photo |

|

| 1965 aerial photo - the Station is gone but the tracks remain |

|

| 2014 aerial photo |

Here is another useful comparative photo of the same spot, taken about 50 years apart. Unfortunately Bruce Chapman's photo below was taken just a few years after the Station was demolished.

|

Photo taken in the mid-1960s behind Fentiman's. Westboro

Station would have been on the left side of the photo,

but at this point is just a field of overgrown grass.

Photo courtesy of the amazing Bruce Chapman collection. |

|

Here is close to the same view in behind the Fentiman's

building at the north end of Roosevelt, circa 2015. The

sidewalk alongside the Transitway are more or less on the

exact spot of the railway tracks, placing the Station directly

overtop of what is now the Transitway trench. |

Lastly, Andrew King on his blog in 2014 (

https://ottawarewind.com/2014/11/30/remains-of-140-year-old-canadian-pacific-railway-on-ncc-parkway/) made a great photo merge using the Mattingly photo at the top of this article, and the house on Workman in behind which still exists today to place Westboro Station:

|

| Sourced from Andrew King, Ottawa Rewind |

|

| Sourced from Andrew King, Ottawa Rewind |

Well, somehow this started out to be a shorter article, but somehow the pieces came together making this a rather thorough history. But a worthwhile look at this great feature of Westboro which helped develop the neighbourhood and helped greatly improve travel and industry during those key fourty years. In a way it's sad that the station had to be demolished, how neat would it be if it still stood in its place, perhaps as a unique residential home! Thankfully there are still many towns in Ontario where the old stations have been preserved, and it is a treat to visit one and imagine it as a bustling centre of activity in the golden age of rail transportation. I thank my contributors and sources very much for helping make this great story easy to put together.