Dave Allston's blog about west Ottawa's little-known history, with stories, photos and information covering the fascinating history of the historic Kitchissippi neighbourhoods.

Tuesday, January 23, 2024

Live Presentation "Ottawa's Shoreline ... Built from Garbage?" this Saturday!

Friday, January 12, 2024

The Story of Sam Gordon - Memorable Early Westboro Teacher

(This is the first of what I hope will be a series of articles about life in Westboro in the 1850s)

Today Westboro is home to many large schools, and dozens of excellent teachers helping educate the roughly 2,000 kids that attend these schools. But today I want turn back the clock 170 years to primitive Westboro, when the neighbourhood had just one school, with one room full of kids of all ages (who travelled in from all over the area), and most notably for the sake of this story, one teacher.

I wrote about the early days of schools in Kitchissippi a few years ago (check out that story here) and in the article, I wrote about the first school, which was established in 1851 in what is now Westboro, on land donated by the Thomson family (who built Maplelawn, aka the Keg Manor home).

The Thomsons donated a 66' x 99' piece of land in 1851, in the heart of what would one day be Westboro, but at the time was simply part of the wilderness of Nepean Township. The name Skead's Mills was still years away, and the early names of Baytown and Birchton would come later too. The land really was in the middle of nowhere. Even All Saints Church was still 14 years away from having its cornerstone laid.

|

| 19th century frame school house. (This is not in Westboro, but an example of what it may have looked like. This is actually Jockvale School, also in Nepean Township, circa 1889). (Source: Nepean Museum) |

The school was built on what is now the northwest corner of Richmond and Churchill (where Gezellig's is now located), and would have looked not unlike the school depicted above. Today's Churchill Avenue Public School traces its origins back to this 1851 school.

Very little is known about this original school house, or even the brick one that replaced it in 1866 when the first one was apparently beginning to fall apart.

So that makes it all the more exciting that I stumbled across a really great story about the school from the 1850s. I mean, any story about Kitchissippi from that era is rare and exciting, but this one brings alive such a cool early days story that I just had to share it.

It's all thanks to an interview the Citizen did in 1927 with an elderly Ottawa resident, James McIsaac, who had attended school in Westboro in the 1850s, and remembered fondly one of the teachers there from that time, Mr. Sam Gordon.

The story is set during the years 1856 and 1857 while James McIsaac was a young 8-9 year old student at the school.

Now at the time, most of the teachers in Nepean Township were male. And the school had just one room to accommodate the 20 to 30 students in attendance (the earliest figure I have is 29 students who attended in the 1863 year, which is a few years after this story is set, so the number of students attending in the mid-1850s was likely even smaller). The student population would have been made up of children from west end farms stretching from Woodroffe to Bayswater, from the Ottawa River all the way south to Baseline. This was what was known as Nepean Township "school section 2". It was just farms, and at the time in the mid-1850s, only half of the land, if that, was even occupied.

Sam Gordon had come to Bytown from Ireland in the early 1850s, part of the large number of Irish relocating to Canada at the time, largely due to the potato famine. He was a college graduate, and had been the head of an academy of some kind back home. He was in his fourties, and unmarried. It was on his very first day of school in Westboro that the mysterious Irishman caught the attention of his group of farm kids.

Sam had been brought in as a replacement teacher and on his first day, upon arriving at school, the students noticed a new fiddle hanging on the wall.

"When recess came the pupils ran helter-skelter into the yard", recounted the Citizen. "Soon through the open door they heard what Mr. McIsaac describes as the most beautiful violin music. One by one the pupils crept back into the school and sat listening spellbound to the strains that came from the master's fiddle."

"Well, children", Gordon said at the conclusion of his piece, "you evidently like music. I love it, so we will have plenty of it."

And they did. From then on, every day at recess, Gordon would play his fiddle for the children. As well, on every Saturday afternoon, Sam had all the children back for what he called the "school house cleaning", where he would play more music. Barn dance music was mixed with music "which made many of the children cry, it was so sad and solemn." Eventually, Sam taught the children drill and fairy dances on these Saturdays, all to the music of his violin. "Ah, those were the days", recalled McIsaac.

McIsaac noted though that before there was music, there was work. "The boys carried water from the school well, and the girls swept and scrubbed the school floor. The soap and brooms were bought with money brought by the children from home. Now wasn't that nice? It gave the little ones a real sense of ownership in the school."

|

| "The Village School in 1848" painted by Albert Anker |

Sam Gordon was also an artist, and drew on the walls and in the children's books. He drew "the most beautiful sketches of landscapes, of cows in the nearby fields, of the children themselves, of the schoolhouse, and of all sorts of pretty things", remembered McIsaac. "This old bachelor seemed to have a beautiful soul and the children all loved him."

Gordon was unique for the era. The Citizen called him "a teacher who ruled by love and the power of music at a period when other teachers ruled by physical force." There was a ruler and a strap present in the school, said McIsaac, but they were seldom, if ever used.

But the use (or at least the threat) of physical force by teachers at the time was usually necessary. Male students attending school in the country were often the sons of farmers. They were often physically big and very strong, having put in many years of hard labour on the family farm. And they could be as old as 25 attending school in that era. The Citizen compared them to the supervisors of lumbering jobs in the forest:

"The old time school teachers (forties to sixties) were nearly all what in the vernacular might be called cards. Most of them had oddities of manner and action which will make them long remembered. They had also a vigor of action which made them celebrated. In many ways they were in a class with the bush foremen of the fifties and sixties. Both had to hold their jobs by force. Both had to be supreme, no matter how. If the big boys ran the school, the teacher had to resign and teacher jobs were not numerous. The bush foreman had, on his part, to handle men who were rough and ready and who would just as soon fight as eat. Some of them would sooner fight than eat. Some of them were larger physically than the foreman, and if the foreman resorted to questionable methods of holding his job, he had cause for excuse."

So back to Sam Gordon, his value to the kids was never more apparent than from one time when he fell ill for a period of time, and a temporary teacher was brought in to the Westboro school house. The replacement teacher was a larger man of about 50 years of age. "After this chap had been in the school a couple of days, the pupils all knew just how much they really thought of Sam", said McIsaac.

The new teacher came from somewhere in the country, or perhaps Bytown, McIsaac couldn't remember clearly. But he recalled that he walked in to work each day, carrying with him a bundle which contained his lunch. Each morning upon arrival, he would place the bundle up in the school loft through a trap door.

The replacement teacher also apparently had a habit of falling asleep mid-class with his head on the desk.

"Well it was not long before the children discovered how soundly the temporary teacher slept. One day two of the larger boys had the temerity to get on the teacher's desk and by mutual aid succeeded in getting the teacher's bundle down from the loft", recalled McIsaac. "Then they went out to the road and put the bundle on a load of logs which was being taken to Bytown."

"The boys were back in their place before the teacher woke up. When the teacher looked for his bundle at noon that day there were lots of excitement", joked McIsaac.

"It was noticed that then next day the teacher took only 40 winks, so to speak, and the day after that Sam Gordon came back and all was well."

McIsaac shared another remembrance of another temporary teacher who filled in at one time, a younger man, who was studying for the ministry, and who lived along the Rideau River. McIsaac recalled he had a "marked dislike" of dust inside the school. As Richmond Road was a dry dirt road at the time, particularly in the heat of the spring or early summer, and as the school faced Richmond Road, dust that was kicked up by the road would constantly find its way inside the school.

"He was a kind teacher, but his habit of always flecking dust off his clothes and polishing his desk sort of got on the nerves of the children."

What a neat glimpse into the long lost days of very early Westboro!

As records are so sparse from the era, I could not confirm who Sam Gordon was, or definitively confirm where he went after his time in Westboro. It appears likely that he is the same Sam Gordon who a few years later was teaching in Goulbourne Township, in school section 2 there. The 1863 Superintendent's report to Carleton County Council noted that Samuel Gordon was their teacher, with 48 pupils, in a log school house.

Old records of Goulbourne Township in the 1860s also list a Samuel Gordon living and farming in Munster Hamlet, but with a sizable family. As our Westboro Sam Gordon was a bachelor without children, it seems unlikely the Munster Sam Gordon is the same one. And with the commonality of the name, I can't connect him definitively to any records. So the trail simply goes cold.

However, it's clear the influence Sam Gordon had on that group of early west end children, particularly when you consider how 70 years after the fact, James McIsaac was able to recount with such incredible detail the man who had left such an impression on him as a youth.

So, it appears this story remains just that - a tidbit of school life in Westboro so long ago. And it is thanks to the interview with elderly McIsaac in 1927 that this story is preserved and can now bring Sam Gordon to life again, 170 years later.

|

| "The Violinist" - Alson Skinner Clark |

Tuesday, December 12, 2023

A 1940s Christmas at Byron House

For the December issue of the Kitchissippi Times, I've written about a local history story that has unfortunately become lost to time.

One of the most impressive homes on Island Park Drive played an important role during WWII! Read all about "Byron House" at https://kitchissippi.com/2023/11/30/early-days-a-1940s-christmas-at-byron-house/

|

| Byron House/Kirkpatrick House in 1940 |

Bonus content! Incredibly, a telephone call from July 1941 made by two of the children at Byron House on Island Park Drive back home ot the UK was recorded and preserved by the BBC. You can hear a snippet of this call from Polly and Geoffrey Carton at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/teach/school-radio/history-ks2-world-war-2-clips-children-evacuated-abroad/zby4bdm

I've also amazingly tracked down video footage of the children at Byron House in an archive in the UK. I'm working with an archivist there to hopefully acquire this film footage (I have no idea how long it is, or what it shows), but I think it would be amazing to see some video of the house and the children enjoying it 80 years ago. Fingers crossed I'm able to get ahold of it soon.

|

| The Byron House children out front of 539 Island Park Drive |

|

| The Byron House children work on a miniature model of Island Park Drive as part of a school project in 1940 |

Sunday, December 3, 2023

Kitchissippi's Heritage over the last 20 years & the urgency of what's coming next

My November article for the Kitchissippi Times is an important one. I usually cover a single topic or event for the Times, but this month, as it was the 20th Anniversary issue for the Times, I chose to write about how heritage has evolved in our neighbourhoods over the last twenty years. But more importantly, how heritage is severely threatened by Ontario Bill 23, which in a year's time will effectively render almost all of our most heritage-worthy (but not-yet-designated) buildings exempt from designation.

This is an issue which is getting hardly any attention in mainstream media. Maybe because there's still another year to go until it becomes a real problem. But that year will go quickly, and by then, or even six months from now, it will be too late.

Please read the article to learn more about what we stand to lose not only in Kitchissippi, but across Ottawa and the province as a whole.

The only solutions are to cross fingers and close our eyes and hope the provincial government changes its mind about the heritage registers (not likely, maybe not even possible now); to ignore it and just let it happen and see so many heritage designation-worthy buildings be torn down and there will be nothing we can do about it; or we can act now and pursue designation of those buildings we deem most important to maintain.

As part of the article, the Times filmed me giving a little 15 minute guided tour of Kitchissippi's most heritage-worthy buildings, with a few quick facts and details about a few of them. You'll find the video at the bottom of the article, or you can view it directly on Youtube at:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WhYUjRwJkRk

I know the City and our councillor Jeff Leiper, as well as each community association in Kitchissippi, are taking steps to review what might be possible, and to prioritize which buildings ought to be reviewed for designation. I wrote up a detailed report myself for Jeff's office, and included a "top 25" list for his consideration, and I'll be speaking with all the community associations next week about it, and offering my help. But it will take a lot of community input to help push this along. It's a mad scramble, and it's a mess, but this is what we're stuck with.

If you'd like to provide your input, the City is asking for it! Check out this link for how you can contribute: https://engage.ottawa.ca/reviewing-heritage-register

More to come!

How garbage helped build the parkway and saved Mechanicsville

This fall, I wrote a two-part column for the Kitchissippi Times on how garbage was used to fill in three bays on the Ottawa River, between Mechanicsville and LeBreton Flats, creating artificial land. That land was primarily used for the creation of the Kichi Zībī Mīkan (Ottawa River Parkway), but much of it still remains unused, awaiting potential future use by the NCC for embassies or who knows what at LeBreton.

Part one I previously posted here in the Museum (https://kitchissippi.com/2023/09/11/early-days-from-landfill-to-useable-land-how-the-ottawa-river-shoreline-was-built-using-garbage/).

This is part two: https://kitchissippi.com/2023/10/25/early-days-how-garbage-helped-build-the-parkway-and-saved-mechanicsville/

Part two focuses on Lazy Bay, and how this popular water spot was filled in, which may have actually saved Mechanicsville. If it wasn't for filling in the Bay, the Parkway may have had to run much further south, which would have cut significantly into the housing of the neighbourhood. And honestly, that wouldn't have been seen as that bad an option to City Council, who considered the whole of Mechanicsville for major urban renewal at the time. A huge 1960s project would have seen the entirety of the neighbourhood torn down a la LeBreton, and replaced by apartment blocks. Thankfully this was avoided, in part due to the filling of Lazy Bay.

The building of the National Arts Centre also played a key role in filling in these bays, and you'll want to read about the astonishing fact that less than a year after garbage was dumped indiscriminately in to the bays, expensive contracts were let to remove some of the garbage! (But only in certain areas, certainly not the full length of the Ottawa River).

I plan on writing a "part 3" over the Christmas break (exclusively here for the Museum) on what all this means today, and what water and soil testing and sampling has shown over the last 20-30 years. The results are interesting, and I put in quite a bit of time in the fall digging in to the results. So more to come on that soon.

Note, I will also be making a presentation about this whole topic, which will feature many visuals/photos/etc. for the Historical Society of Ottawa on Saturday January 27th. It will be at 1 p.m. but will NOT be broadcast online I don't think. It will be an in-person Speaker Series event at the auditorium of the Ottawa Public Library. I don't believe you need to be a member of the HSO to attend, but I certainly encourage you to consider taking out a membership to help this valuable group, and the work they do to help promote and preserve heritage in Ottawa.

Please enjoy part two and perhaps I'll see you in January!

|

| Lazy Bay-Bayview Bay-Nepean Bay in 1928 |

|

| The same three bays in 2022 |

Thursday, September 14, 2023

Creating land: How the City's garbage became the new Ottawa River shoreline

|

| lookng east from Bayview, November 1962 (source: City of Ottawa Archives, CA-8684) |

While conducting research for my book on Mechanicsville, I began looking at the history of Lazy Bay, and the "Lazy Bay Commons", as a portion of the abutting land is sometimes called. For those of you who don't know the term, Lazy Bay is the little bay that comes in from the River alongside the Parkway, just north of Laroche Park. Lazy Bay Commons is the greenspace south of the Parkway, on which the NCC is proposing the construction of a row of embassies.

Prior to doing this research, I'd known that when the Parkway was first built, that the City and NCC had built up areas along the shoreline to help ensure a relatively straight line of travel, close to the river, to take advantage of the picturesque views. In order to do this, a large area in the LeBreton Flats, Bayview and Mechanicsville areas (as well as an area closer to McKellar and Woodroffe) were filled in. I also knew that rock was brought in to create the base. And probably like most people, that's about all I really knew. Yes I'd heard the rumours of old garbage dumps or pits along the route, and probably like most people, assumed it was just old temporary dumps that had existed in LeBreton or the open areas around Bayview.

However, as I dug deeper in to the research, I discovered that in fact, the story was far more complex. That the story of the Parkway and the created land over which it travels, from Mechanicsville east through LeBreton Flats, has many interconnecting parts to other major NCC and City of Ottawa projects happening at the time. Most notably - the shifting of all city garbage dumps and collection from the west and east ends - to the shoreline of the Ottawa River. Yes, in the early 1960s, the city garbage trucks brought their loads to the shore; ordinary citizens brought their old fridges and televisions and bags of trash; and many of the houses of LeBreton Flats, exprorpriated as part of the "urban renewal" of the neighbourhood, were discarded just a few hundred feet away into Nepean Bay.

My September column in the Kitchissippi Times introduces this topic, and the history behind the Parkway and how the new land was created. This was not just an Ottawa concept, cities across North America were doing the same thing. And the short-sighted solution to solving problems at the time, are now wreaking havoc 60 years later as plans are made to build on these articifically-created landfill sites, including most notably at Lazy Bay Commons.

|

| Ottawa Citizen - March 8, 1963 |

This article is part one of a two-part series (part two will run in October), and it really only scratches the surface of the whole story, but I think gives a good overview. Please read the full story at the link below:

Note that in the printed/paper version of the newspaper, an error was printed, giving the date of one of the photos as 1968. That is incorrect, it was from 1962. It is fixed in the online edition.

Also, the perils of writing for a print newspaper meant that I had to cut down a lot of content into about 1,600 words, which my editor further edited down to fit. One quote I really liked that got removed I'm going to re-add here, from near the end of the article, discussing the problems in LeBreton Flats as families left their expropriated houses, and they were left boarded up and vacant:

Though the first houses began to be demolished in October 1963, Ottawa’s Fire Chief urged it wasn’t happening fast enough, and pressured the NCC, calling the houses “time bombs ready to go off”. The Journal wrote of the boarded up homes: “They’ve been taken over by drunks who wine-and-dine and sleep at their leisure, children who play in the ghostly rooms and sheds, and scavenger junkmen at work, systematically stripping them of everything saleable.”

The NCC quickly began pulling down the houses, and placing them in the Bay. Many of the original LeBreton Flats houses still exist today – buried deep below the Parkway.

Monday, June 12, 2023

Goodbye 226 Carruthers Avenue - A profile

|

| October 2020 - Google Streetview |

|

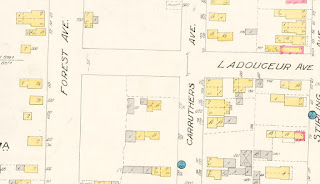

| 1912 Fire Insurance Plan |

|

| Ottawa Citizen, August 18, 1916 |

|

| 226 Carruthers Avenue - May 2023 (Photo by Dave Allston) |

|

| Proposed three-storey, three-unit building (Source: Fotenn Planning + Design, Twitter) |

.jpg)